GRASS HOUSE STUDIO

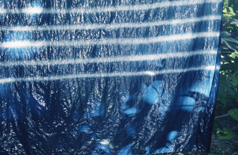

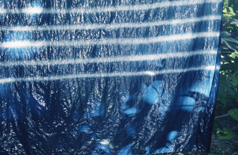

QUILTS MADE FROM FABRIC OR FIBERS I DYED MYSELF

I first visited the tropical island of Bali in 1983. Every breeze carried the sound of rustling coconut leaves, and offerings of flowers and incense lent vibrant color and a sense of peace. I began to experience a different flow of time, to discover a world I had never seen or heard of before. With every trip I made to Bali my dream of one day opening a studio there grew stronger.

Work on the studio began in 1989, in a corner of a palm grove in the quiet village of Kesiman, which lies among the hills inland from Sanur. The first tasks were to dig wells and plant trees on what had been fields of tapioca. After that, I had four goals: to protect the environment, to convey the essence of south Asia as I'd come to know it in my travels, to find a design that would allow for optimal wind passage between the buildings, and to create a living space that blended in with the nature around it. The building materials were taken as-is from nature: stones transported from the high mountain in the middle of the island, grass growing wild in the hills, palm trees, bamboo, roof tiles of unglazed earthenware, huge rocks from the bottom of the sea, coral from the atoll.

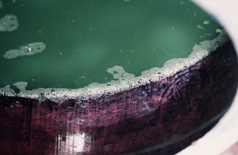

As construction moved along, I made many discoveries about the rhythms and materials of nature, acquiring traditional techniques and wisdom from the past while working alongside modern villagers and artisans, For the roof we wove a giant tapestry of grass and bamboo, and with bits of coral we made a stony quiltlike pattern on the outer wall. We laid down small stones in a spiral pattern on the floor of the entryway. When construction was completed at last, I named it "Grass House Studio."

In Bali, people's lives revolve around events in the calendar, and New Year's, or Galungan, is the most important festival of the year. At every front gate, stalks of cut bamboo about twenty-five feet (eight meters) tall are said to guide the ancestors and gods who at that time of year descend the sacred mountain and enter people's homes. These stalks of bamboo, called penjors, are hung with young palm fronds, little shells that clatter when the wind blows and rontal-leaf decorations that women have cut, folded, woven and tied. Human expertise is added to nature's gifts to make them into offerings for the gods. The preparation of sacred offerings goes on without fuss or fanfare, as quietly as the preparation of daily meals.

At Grass house Studio, my day begins with collecting jasmine flowers that have fallen on the ground. Afterward I burn some fragrant liligundi to fumigate the thatched roof and chase away any small insects that may have settled there. The perfumed smoke drifting idly from the eaves out into the garden is refreshing to the spirit. Over the ground is a scattering of coconuts, no two alike. I break open the hard shell of one and scrape out the meat.

On my land is a small shrine to the gods where morning and evening I set flowers, burn incense and cleanse myself with water before offering up prayers. The aroma of sandalwood is bracing.

Later, as night falls and the studio grows still, I step into the garden to light candles by the stone statues there. Candle glow only deepens the surrounding black. In the pitch-dark of night the senses are heightened and even vision grows more acute. The cries and murmurs of birds and animals, the thuds of falling coconuts, all form part of the unalterable web of the rhythms in nature that lie beyond human control.

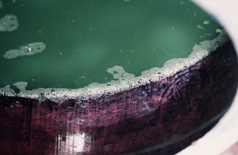

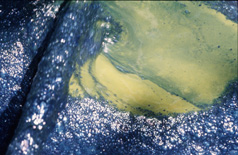

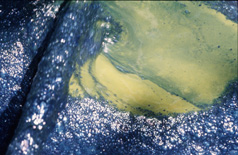

Two seasons alternate on the island, dry and rainy. Sunlight is lavish year-round, and vegetation grows thick. Late at night when the moon is full, large dewdrops hang from the tips of leaves. Gazing at them, I sense the overflowing vitality in plants that sustains so many of the living things on this planet. Colors born from the plant world carry something of the essence of life. It is that vital life force that I work with; that is why I take such pains with the materials for my quilts.

The quilts I create incorporate textures that I have absorbed from overseas. They are woven with contrasting textures of other cultures, shaped by innumerable differences in ethnicity, customs, lifestyle and values. In the early years it often happened that work I had done in Bali proved overpowering and somehow out of place when I took it back to Kyoto; over time I realized that I needed to find the right balance between what I was learning in Bali and my own natural aesthetic and cultural influences. Basically I began to prune away elements that were not strictly in line with my own aesthetic. This process of cutting away has been enlivening. I often feel that I am trying to cut down to the marrow of my work and also, since I work with plants and other natural materials, of life itself.

My work in the Grass House Studio near the equator thus gets close to the bone; it is, literally and figuratively, a start from "zero." Setting up my studio in a foreign culture has been a way of getting closer to fundamentals.

"QUILT ARTISTRY" Inspired Design From The East - Yoshiko Jinzenji

KODANSHA INTERNATIONAL 2008 (ENGLISH VERSION, 2ND EDITION) |